One of the most consequential — and potentially controversial — features of the European Commission’s Digital Omnibus proposal is the introduction of a new limitation to the data subject’s right of access under Article 15 GDPR. The proposal would allow restrictions where “the data subject abuses the rights conferred by this Regulation for purposes other than the protection of their data.”

For many organisations, this language speaks directly to a structural weakness in the current regime. Article 15 GDPR contains few intrinsic constraints on how the right may be exercised, while operational obligations on controllers are both strict and resource-intensive. As a result, organisations face a growing volume of repetitive, strategic, or dispute-driven requests that are only loosely connected to the transparency rationale of the right.

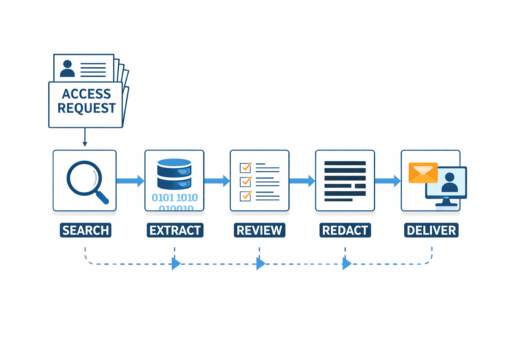

This concern is explicitly recognised in the Digital Omnibus. In its explanatory memorandum, the Commission notes that the abuse of data subject access requests “has frequently been raised as an issue for controllers who are required to dedicate significant resources to responding to abusive access requests.” In practice, responding to such requests involves system-wide data searches, extraction, review, redaction, coordination across systems and jurisdictions, and legal oversight — costs that are substantial and recurring, particularly in labour-intensive or highly regulated sectors.

From an industry viewpoint, the proposed limitation appears to be an attempt to restore proportionality to the access regime. The proposal targets contexts where access requests serve purposes disconnected from data protection, such as litigation strategy, employment leverage, broad discovery exercises, or commercial positioning, even when framed formally as transparency requests.

By signalling that the law may recognise and constrain abusive or strategically instrumentalised access practices, the proposal gestures toward a more sustainable, administrable, and operationally realistic framework. Many organisations will view this as an overdue corrective to a framework whose open-ended obligations have, in some cases, encouraged exploitation rather than accountability.

Any reform to the right of access must be assessed in light of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights (CFR). Article 8 CFR guarantees the right to the protection of personal data, including access to data concerning oneself. Further, Article 52(1) CFR, any limitation on a Charter right must:

The proposed restriction must therefore be evaluated not only in terms of administrative practicality, but also with regard to whether it:

The central challenge to determining when a request is abusive lies in the meaning to be drawn from the operative language. What does it mean to act for purposes “other than the protection of their data”? Does this include circumstances where the individual’s objectives are mixed — for example, where a request is connected to employment, consumer, reputational, or legal disputes, but the person still seeks meaningful information about the processing of their data?

Likewise, the term “abuse” is inherently open-textured. Without clearer statutory criteria, it risks beingdrawn too narrowly, neutralising its effect, or drawn too broadly, enabling controllers to reject requests that are burdensome but nonetheless engage the transparency function of Article 15.

From the standpoint of Article 52 CFR, this vagueness matters. The Court of Justice consistently requires that restrictions on fundamental rights be clear, predictable, and reviewable, so individuals can understand when and how their rights may be limited and so that arbitrary interference is avoided. A broadly framed concept of “abuse” may struggle to satisfy that standard unless later regulatory or judicial guidance supplies precision.

The Charter also requires that the essence of the right remain untouched. For the right of access, that essence is commonly understood as the individual’s ability to:

If the new clause were applied in a way that excludes requests merely because they arise in contentious or strategic contexts, there is a risk that access may be denied even where the substantive transparency interest remains real. In such scenarios, the restriction could drift from legitimate limitation toward structural erosion of a core accountability mechanism.

This is the fault-line on which the amendment will be judged: whether it targets only access requests that are functionally disconnected from the right’s purpose, or whether its breadth makes it difficult to guarantee that the right’s essence remains preserved.

A defensible proportionality rationale can nonetheless be articulated. Preventing the abuse of access rights may serve:

If the clause were narrowly interpreted, limited to cases where the exercise of the right bears no meaningful relationship to the protection or understanding of personal data, it could plausibly be seen as respecting the essence of Article 8 CFR, while ensuring that the limitation of the exercise of the right remains necessary and proportionate in practice, consistent with Article 52(1).

The difficulty is that the current drafting does not itself impose those limits, instead leaving the balancing exercise to future controllers, regulators, and courts, with inevitable uncertainty and litigation risk.

The Court of Justice has the opportunity to join the debate on proportionality and data access rights in the upcoming judgment in Case C-526/24 (Brillen Rottler), The Advocate-General’s opinion, issued in September 2025, tends towards maintaining few, if any, limits on the right of access. Given the facts of the case, where the abuse of access rights appears obvious, it is clear there is a long way to go before arriving at a workable solution.

For any reform to have constitutional durability, and practical usefulness, it will likely turn on whether the notions of “abuse” and “purposes other than the protection of their data” are ultimately narrowly delineated, applied with discipline, and anchored to preserving the essence of the right in line with Article 52 CFR.

Clearly, there is a need for greater precision on the meaning of the terms being applied in relation to data access rights. If that precision emerges during the current legislative debate, the reform may help restore a more sustainable balance between accountability and operational reality. If not, the clause risks being seen as too vague and open-ended to satisfy Article 52 CFR, and the debate over proportionality, necessity, and the preservation of the core right will only intensify.

The Digital Omnibus proposal acknowledges a real and pressing operational concern, one the Commission itself recognises as imposing significant, recurring costs on organisations required to respond to abusive access requests. It points toward a model more fitting to today’s hyperconnected world in which the right of access, as provided in the CFR, is preserved. However, the right of access needs to be exercised within clearer and more proportionate boundaries aligned with its core transparency function and work effectively in practice, to minimise abusive access requests.

15 January 2026