The European Union’s framework for judicial cooperation has evolved significantly over recent decades, reflecting the increasingly transnational character of serious crime. Within this framework, Eurojust performs a central coordinating function, supporting national authorities in the investigation and prosecution of cross-border criminal activity. The effectiveness of Eurojust’s mandate, however, depends in part on the availability of legally certain mechanisms for exchanging operational personal information in its cooperation with third countries.

The 2025 evaluation of the Eurojust Regulation by the European Commission identifies persistent constraints affecting international cooperation, most notably the limited availability of adequacy decisions under Article 57 and legally binding international cooperation agreements under Article 58(1)(a). These provisions constitute the principal legal pathways through which Eurojust may exchange personal data with non-EU partners. Their practical application is therefore directly linked to the operational capacity of Eurojust in an international context.

Adequacy decisions under the Law Enforcement Directive (LED), available for use not only by Member State law enforcement authorities but also by Eurojust, are designed to ensure that personal data transferred to third countries remains subject to safeguards that are essentially equivalent to those guaranteed within the European Union. In principle, this mechanism provides a balance between legal certainty and a high standard of protection for fundamental rights. In practice, however, the number of adequacy decisions adopted under the Directive remains highly deficient. To date, only the United Kingdom has been recognised as providing an adequate level of protection for the purposes of the LED. The United Kingdom’s position is widely understood as reflecting its prior status as a Member State of the European Union and its historical alignment with EU data protection standards.

Nearly eight years after the entry into force of the LED, no additional adequacy decisions have been adopted by the European Commission. This situation hints at a structural problem that warrants careful consideration, particularly in light of the European Union’s policy objective of strengthening international cooperation in response to transnational crime. While multiple factors may be contributory, the main problem concerns the structural alignment between the Law Enforcement Directive and the General Data Protection Regulation.

However, the replication of GDPR-style safeguards into the law enforcement domain introduces complexities arising from the differing institutional and operational environments in which these regimes function. The GDPR was developed primarily within a commercial and consumer protection context, addressing risks associated with private-sector data processing. Law enforcement data processing, by contrast, is conducted by public authorities operating under statutory mandates, procedural constraints, and judicial oversight mechanisms. These distinctions do not diminish the importance of robust data protection safeguards, but they may influence how regulatory obligations are interpreted and applied in practice.

A related consideration concerns the interaction between the requirements introduced by the LED and safeguards already embedded within EU and national criminal justice systems. Many protections relevant to the handling of personal data are integral to criminal procedural frameworks. These include rules governing the lawfulness of evidence collection, standards of relevance and proportionality, judicial authorisation requirements, confidentiality/security obligations, and various oversight mechanisms. The LED introduces additional regulatory obligations in areas such as data security, logging, data quality, and accountability. While these obligations reinforce formal protections, their relationship with pre-existing procedural safeguards may generate interpretative and operational challenges.

Such complexity may be particularly relevant in the context of cross-border cooperation. International data exchanges require legal certainty, clarity of obligations, and administrative efficiency. Where regulatory requirements overlap with procedural safeguards operating under different legal logics, competent authorities may encounter increased compliance burdens and legal uncertainty. These effects may influence both the timeliness and predictability of cooperation processes.

The concept of essential equivalence, which underpins adequacy assessments, presents an additional area for reflection. Third countries are required to demonstrate safeguards comparable to those provided under EU law. Given the distinctive nature of the GDPR and Law Enforcement Directive framework, many third countries do not replicate EU-style provisions in a directly comparable form. However, divergence in legal architecture does not necessarily imply the absence of effective safeguards. Third-country legal systems may provide protections through alternative mechanisms, including constitutional rights frameworks, criminal procedure guarantees, judicial supervision, sector-specific legislation, and institutional oversight bodies.

A predominantly formal comparison based on structural similarity may therefore encounter difficulties in capturing functional equivalence across diverse legal systems. In this context, consideration may be given to assessment methodologies that place greater emphasis on the effectiveness of safeguards in practice. A context-sensitive approach could evaluate whether third-country systems achieve comparable protective outcomes, rather than focusing primarily on textual alignment with EU regulatory structures. Such an approach would not alter the objective of ensuring a high level of data protection, but it may contribute to greater clarity and predictability in adequacy determinations.

These considerations have direct implications for Eurojust’s cooperation framework. Adequacy decisions under Article 57 play a significant role in shaping Eurojust’s ability to engage with third countries. Where adequacy decisions remain limited, Eurojust must rely more extensively on alternative mechanisms provided under the Regulation, including international agreements and essential equivalence assessments. These mechanisms remain important components of the cooperation framework but may involve more complex or resource-intensive processes. The broader adequacy environment therefore has practical implications for the scope of international partnerships, the degree of legal certainty in data exchanges, and the administrative efficiency of cooperation arrangements.

The protection of personal data in the law enforcement domain remains a core requirement of EU law. At the same time, effective international cooperation is essential for addressing transnational criminal activity. These objectives are not inherently conflicting. Their alignment depends on regulatory frameworks that are both protective and operationally workable. A reassessment of adequacy criteria under the LED, particularly with regard to functional and systemic safeguards, may support enhanced legal certainty, reduced interpretative complexity, and more predictable cooperation pathways.

The evaluation of the Eurojust Regulation provides an opportunity to reflect on the broader legal ecosystem governing international cooperation. In particular, the experience of adequacy decisions under the Law Enforcement Directive suggests the potential value of context-sensitive assessment methodologies, greater recognition of functional safeguards, and enhanced predictability in adequacy determinations. Such considerations may contribute both to the protection of fundamental rights and to the effective functioning of EU judicial cooperation mechanisms.

13 February 2026

On 28 January, 2026, to mark Data Protection Day, the European Data Protection Supervisor (EDPS) and the Council of Europe hosted their annual conference with the theme “Reset or refine?” The question comes at a critical time, as the EU is undertaking significant legislative reforms in the fields of digital, data, and AI. At the centre of this debate is the European Commission’s Digital Omnibus package and the various proposed amendments aimed at simplifying aspects of GDPR.

Throughout the day, it was clear that opinions on these reforms are far from uniform. The Commission is emphasising that the reform process is about simplification, to better support innovation and competitiveness while maintaining the protection of fundamental rights. Alternative views were expressed that the Commission’s proposals will result in a diminishing of data protection rights. So the debate on whether or not we are refining or resetting data protection rules in the EU will continue, showing the need for diverse voices to be part of this debate.

A significant point of contention is the Commission’s proposal for a definition of “personal data”. This proposal is based on the September 2025 judgment of the Court of Justice of the EU (CJEU) in the case of EDPS v SRB (C-413/23 P). The Commission argues that the proposed amendment simply codifies existing definitions in light of decisions by the CJEU. Yet, there were diverse perspectives at the conference. Some attendees raised concerns that the changes might be overly broad and potentially misinterpret the court’s ruling, particularly regarding when pseudonymized data should be considered non-personal and thus exempt from GDPR. Others, however, felt that a compromise could be reached, highlighting the complexity of the issue as the discussions progress through the legislative scrutiny of the Digital Omnibus.

The impact of any legislative reform upon the data protection rights in the EU was a constant theme throughout the day. The Deputy Chair of the European Data Protection Board (EDPB), Jelena Virant Burnik, emphasised that while a full-scale reset of GDPR is unwarranted, some refinements could be beneficial. Other speakers were highly critical of the existing condition of data protection rights and expressed the view that the proposed reforms will only worsen the situation.

Attention was given to the proposed adjustments to cookie consent and the challenges of keeping regulations in step with the evolution of online tracking practices. Civil society voices robustly critiqued these changes, arguing that the proposals could undermine fundamental user rights to privacy and data protection. In contrast, industry representatives argued that such adjustments would provide the necessary legal clarity around consent, supporting business activities and innovation in Europe.

Wojciech Wiewiórowski, the European Data Protection Supervisor, made clear in his keynote address that reform processes require widespread engagement and discussions. The EU institutions need to talk with each other, and the voices of all in society need to be heard.

Privacy Next will be closely tracking the Digital Omnibus negotiations across the EU, so keep up to date on developments by subscribing to our newsletter below.

29 January, 2026

The EU’s Law Enforcement Directive 2016/680 (LED) was adopted as the criminal justice counterpart to the General Data Protection Regulation. The objective was to ensure a common and consistent level of protection for personal data processed by police, prosecutors, and judicial authorities, while enabling effective cooperation within the European Union and beyond. Yet nearly ten years after its adoption in 2026, the gap between that objective and the reality experienced by criminal justice authorities has become increasingly stark.

What was intended as a modern, enabling framework has instead evolved into a significant structural impediment to the effective prevention, detection, investigation, and prosecution of crime. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the fight against serious and organised crime, including drug trafficking, human trafficking, and transnational criminal networks that operate with speed, secrecy, and technological sophistication. The uncomfortable truth is that the LED, as currently designed and interpreted, is not merely imperfect; it is actively hampering the operational effectiveness of those tasked with protecting public safety.

At the heart of the problem lies a fundamental legislative misjudgement: the decision to transplant data protection concepts and principles, developed primarily for consumer protection, into the different environment of criminal justice, without sufficient recalibration. The absence of recalibration has produced a framework that prioritises regulatory symmetry regarding personal data over the operational realities of criminal justice. The consequences have been limits on the ability of the criminal justice system to uphold the safety and security of society.

From its inception, the LED was framed as part of the EU’s broader data protection reform package. Negotiated alongside the GDPR, it was shaped by a powerful impulse toward legal and practical consistency in data protection. Concepts such as purpose limitation, data minimisation, storage limitation, data subject rights, and restrictions on international data transfers were deliberately aligned across both instruments. This alignment was presented as a virtue: a coherent EU data protection “family” of laws, including also the slightly later (2018) EU Data Protection Regulation (EUDPR) for data processing by EU Institutions.

Yet this coherence was achieved at the expense of contextual understanding. Data processing in criminal justice is not a variant of commercial data processing; it is a fundamentally different activity. By failing to operationalise this distinction, the LED inherited assumptions that do not hold in criminal justice.

For effective operational capacity in law enforcement, authorities require rapid, flexible data exchange to respond to transnational crime, terrorism, and cyber threats. Yet the directive’s procedural safeguards, consent requirements, and limitations on data use have slowed down these processes. Instead of building a seamless network of cooperation, the directive has created obstacles that discourage proactive information sharing, thereby impacting law enforcement and judicial cooperation.

For example, Article 6 LED creates complications requiring clear distinctions to be made for different categories of data subjects. This applies to suspects, those convicted, victims or individuals who may be victims, and other parties to a criminal offence. When it comes to suspects, other parties, and individuals convicted, strict differentiations of categories are not easily possible, as these roles are often fluid or overlapping. The result is an administrative burden of constant updating of the categories, which in turn delays investigations and complicates the exchange of intelligence between Member States.

Another example exists with Article 7 of the Directive, calling for data accuracy, whereby a distinction is to be made between “factual” versus “opinion-based” reporting. Given that law enforcement work inherently relies on subjective witness accounts and preliminary leads developed through experience-based intuition, requiring officers to document and verify these distinctions to a high data-protection standard hinders operations. Full adherence to Article 7 impacts the rapid sharing of information and intelligence, which is often critical in the early stages of serious crimes, counter-terrorism or organised crime investigations.

A more in-depth discussion on such anomalies can be found here.

This does not mean that striving to ensure data protection in criminal justice should not be an objective to be pursued. The point is that adopting a commercial-based standard designed to uphold consumer rights does not easily translate into the operational realities of criminal justice. Criminal justice systems across the EU already have a range of safeguards addressing privacy rights and evidentiary standards through national, regional, and international human rights standards that are applicable in the processing of personal data in crime and judicial matters. These standards also have oversight authorities through the judicial systems of the Member States, which have specific criminal justice standards to uphold. While the LED may be seen as positive for raising data protection across society, it has not delivered the intended improvements in law enforcement or judicial cooperation.

The most acute and damaging manifestation of the mismatch in applying commercial/consumer regulatory approaches to criminal justice is found in the LED’s rules on international data transfers. Transnational cooperation is the lifeblood of modern law enforcement. Organised crime does not respect borders; it exploits them. Drug supply chains, terrorism planning, trafficking routes, financial flows, and command structures span continents, not jurisdictions. Effective policing, therefore, depends on the rapid, secure, and trusted exchange of information with partners both within and outside the EU.

The LED approaches international data transfers through a structure closely modelled on the GDPR, emphasising adequacy decisions, appropriate safeguards, and narrowly construed derogations. In doing so, it largely ignores the dense web of existing legal frameworks that have governed law enforcement cooperation for decades. Mutual legal assistance treaties, bilateral police agreements, Council of Europe conventions, and operational arrangements involving EU agencies already embed strong procedural safeguards, including judicial or prosecutorial oversight, purpose limitation tied to concrete investigations, audit requirements, strict rules and criminal sanctions for misuse.

Rather than recognising these safeguard mechanisms as constituting a coherent and robust system of protection, the LED superimposes an additional layer of data protection compliance. Law enforcement authorities are often required to conduct parallel assessments, document transfer justifications in GDPR-style terms, and navigate legal uncertainty about whether long-standing cooperation channels remain lawful under EU data protection law.

This is not a neutral administrative burden. In time-sensitive investigations into organised crime networks, delay is itself a form of failure. Intelligence that arrives too late may be operationally useless. Hesitation in sharing data with trusted partners can fracture joint investigations and weaken collective responses. In some cases, authorities report a reluctance to share information at all, for fear of regulatory repercussions, a chilling effect that criminal organisations are quick to exploit.

The LED’s problems extend beyond international cooperation. More broadly, the impact of the LED has resulted in adherence to data protection standards that exceed what is necessary to safeguard the rights of individuals engaged with the criminal justice system. Data protection is necessary in the course of surveillance, investigations, and cooperation between authorities, but the LED, with its GDPR-style demands, offer little demonstrable additional protection beyond what criminal procedure law already provides.

Criminal justice systems in EU Member States already possess a range of safeguards for suspects, accused, and witnesses. The collection, use, and retention of personal data are governed by detailed procedural rules, judicial authorisation requirements, evidentiary standards, and remedies for abuse. These safeguards are specifically designed to balance individual rights against the public interest in prosecution and prevention of crime. The safeguards begin at the national level, and are overseen by regional measures through the European Convention on Human Rights, and international measures with the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

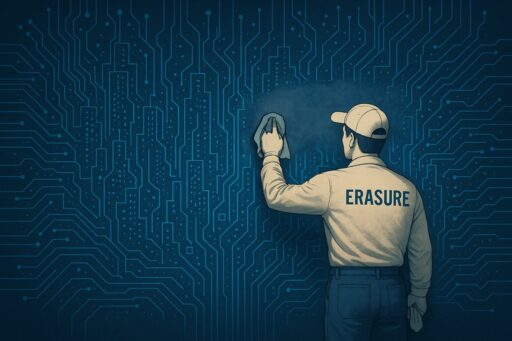

The European and international human rights oversight of criminal justice systems is much better placed and more experienced in applying the necessary proportionality considerations in relation to data protection, in addressing criminal matters. The LED attempts to overlay this landscape with a second, parallel set of obligations that are not always attuned to the realities of criminal justice. Restrictions on data subject rights are formally permitted, but in practice framed so narrowly that authorities must constantly justify what should be self-evident: that access, rectification, or erasure rights cannot be exercised in ways that compromise investigations or judicial proceedings. This has fostered a defensive compliance culture in which law enforcement agencies devote increasing resources to documentation and legal risk management, rather than operational effectiveness.

Crucially, there is little evidence that this additional layer of regulation has significantly improved the protection of individual rights in the criminal justice context. What it has indisputably impacted is the complexity and fragility of the legal environment in which law enforcement operates. Added to this, the absence of common approaches or consistency of application in relation to either the LED or GDPR has created a highly fragmented system where cooperation is very time-consuming for matters of little added value.

What has occurred under the LED is not a careful contextual adaptation, but a form of rights transposition that risks distorting both objectives. Interpretations of data protection rights developed with consumers are increasingly being applied to suspects, organised crime actors, and transnational criminal networks, without sufficient differentiation. Proportionality assessments modelled on commercial data protection do not translate cleanly into investigations where delay can mean lost evidence, compromised sources, or continued victimisation. Transparency obligations that make sense in consumer contexts can, in law enforcement, alert suspects to investigative techniques or expose informants to retaliation. Data protection is a fundamental right in the EU for good reasons, but it cannot be applied across all aspects of society without consideration of the context and the human rights of others in society.

The impact of the LED has placed law enforcement authorities across the EU under mounting strain that is detrimental to addressing serious crimes. Resources are finite. Every hour spent navigating duplicative data protection assessments is an hour not spent analysing intelligence, protecting victims, or dismantling criminal networks. Every delay in cross-border data exchange increases the operational advantage of highly mobile and adaptive criminal organisations.

This is not a speculative concern. Practitioners increasingly describe the LED as an obstacle rather than an enabler. While comprehensive quantitative studies remain limited, the qualitative evidence from operational experience is consistent and troubling. The balance between rights protection and effective law enforcement has tilted too far, to the point where public safety itself is at risk. Even within EU policy circles there is recognition that the Law Enforcement Directive is not working smoothly in practice. The European Commission’s first evaluation report in 2022 acknowledged outstanding issues in the LED’s application, including divergences and data transfer challenges across Member States — and the current 2026 review is explicitly tasked with assessing whether the framework should adapt to technological and operational realities.

It is tempting to view these problems as teething issues, capable of being resolved through guidance, best practices, or targeted amendments. That view underestimates the depth of the problem. The LED’s shortcomings are not merely technical; they are structural. They stem from a foundational choice to model law enforcement data protection on a framework designed for an entirely different domain.

What is required is not fine-tuning, but rethinking and recalibration. A genuinely effective law enforcement data protection regime would start from the realities of criminal justice. It would recognise the human rights protections that already exist in criminal procedure and judicial oversight as primary safeguards. It would treat international law enforcement cooperation as a distinct and legitimate category, rather than a derogation from a market-based norm. And it would articulate a context-sensitive application of human rights protection in criminal justice that protects individuals without paralysing those tasked with enforcing the law.

The forthcoming report by the European Commission on the application of the Law Enforcement Directive, due to be published in May, represents a critical moment. If the review confines itself to questions of implementation and compliance, it will fail to address the real problem. If, however, it acknowledges that the LED in its current form is misaligned with the realities of modern law enforcement, it could open the door to meaningful reform.

Organised crime, drug trafficking, and human trafficking are not abstract policy challenges. They are real, evolving threats that cause profound harm to individuals and societies across Europe. A data protection framework that systematically undermines the ability of law enforcement to respond to these threats is not a success story of fundamental rights protection; it is a policy failure.

The current trends towards upholding a data protection framework created for commercial activity over and above the operational needs of criminal justice have not provided more effective law enforcement or cooperation between criminal justice authorities. Instead, it has contributed to a gradual expansion of regulatory expectations that are increasingly disconnected from operational necessity. Supervisory authorities and courts, acting understandably in a rights-maximising tradition, have little legislative guidance on how to recalibrate these rights for criminal justice realities. The result is regulatory creep, legal uncertainty, and growing hesitation around the use of advanced investigative tools—precisely at a time when criminal organisations are rapidly adopting their methods to new technologies.

As new technologies continue to develop and further regulatory regimes are drawn up, as with AI, the matter is only going to become more complicated. The operational realities of the criminal justice system need greater attention in the development of relevant frameworks to minimise administrative burdens. The EU has the opportunity, and the responsibility, to correct course.

A recalibration of the Law Enforcement Directive is not an attack on data protection. It is a necessary step to ensure that data protection law serves both fundamental rights and the equally fundamental obligations upon the state to ensure the rights of all citizens to security and justice.

22 January, 2026

The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) was conceived as a risk-based framework designed to promote accountability, safeguard fundamental rights, and encourage responsible data practices across the European Union. Among its key mechanisms are the obligations imposed on data controllers in the event of a personal data breach. At present, however, a structural inconsistency exists between Articles 33 and 34 of the Regulation, requiring organisations to apply two distinct risk thresholds when determining whether to notify Supervisory Authorities and affected individuals. The Digital Omnibus proposal seeks to resolve this inconsistency by raising the notification threshold in Article 33 from “risk” to “high risk,” thereby aligning it with the threshold already established under Article 34.

The proposed amendment represents a proportionate and pragmatic refinement of the GDPR’s breach notification regime. It not only simplifies compliance and enhances legal certainty for organisations, but also alleviates unnecessary administrative burdens on Supervisory Authorities and reinforces the Regulation’s underlying commitment to a risk-based approach. Far from diminishing protections for individuals, this proposed reform strengthens them by enabling regulators to prioritise breaches that present a genuine threat to rights and freedoms. Nevertheless, as the proposal remains subject to the legislative process, continued vigilance is warranted to ensure the proportionate and pragmatic refinement is retained in the final text.

Under the GDPR in its current form, Article 33 requires data controllers to notify the relevant Supervisory Authority of a personal data breach unless it is “unlikely to result in a risk” to the rights and freedoms of natural persons. In practical terms, this establishes a relatively low threshold for notification: where any degree of risk is present, notification is typically deemed prudent or necessary. By contrast, Article 34 obliges controllers to notify affected data subjects only where the breach is “likely to result in a high risk” to their rights and freedoms.

This divergence creates a situation in which controllers must conduct two parallel assessments of the same incident, applying distinct conceptual standards. A breach may be judged sufficiently risky to require notification to a Supervisory Authority, yet insufficiently serious to warrant notification to individuals. The resulting interpretive complexity encourages defensive decision-making, with many controllers opting to notify regulators even in cases of marginal or theoretical risk in order to avoid compliance disputes.

Such cases often involve what might be described as “low-grade” or administrative breaches: emails sent to incorrect recipients, postal correspondence delivered to the wrong address, or minor technical errors exposing very limited data for brief periods. These incidents typically present negligible likelihood of harm, particularly where swift mitigation occurs. Nonetheless, the prevailing interpretation of Article 33 has encouraged systematic reporting of such events, generating significant notification volumes across Member States.

The administrative implications are considerable. Each notification, irrespective of its materiality, requires intake, review, and, in many cases, correspondence or clarification. Supervisory Authorities are therefore required to expend scarce regulatory resources processing incidents that pose little or no real-world risk to individuals. The cumulative effect is a system that is procedurally active, yet often substantively inefficient.

The Digital Omnibus proposal addresses this imbalance by amending Article 33 so that notification to Supervisory Authorities would be required only where a breach presents a “high risk” to individuals’ rights and freedoms. This revision would bring Article 33 into alignment with Article 34, replacing the dual-threshold structure with a single, coherent standard.

The legal consequences of such alignment are significant. Controllers would no longer be required to distinguish between “risk” and “high risk” thresholds when determining whether to notify regulators and affected individuals. Instead, a unified assessment would apply across both obligations. This enhances the internal coherence of the GDPR, reduces interpretive ambiguity, and ensures that notification processes are grounded in a consistent conceptual framework.

Crucially, the reform does not eliminate the duty to notify serious breaches. High-risk incidents—such as those involving special-category data, heightened vulnerability, identity-theft risk, financial exposure, or large-scale disclosure—would continue to trigger notification obligations. The proposal therefore rebalances the framework rather than diluting it.

The principal merits of the proposed reform can be understood across three interrelated dimensions: proportionality, legal certainty, and regulatory efficiency.

First, the change reinforces the GDPR’s foundational commitment to proportionality and risk-based regulation. Not all breaches are equal in nature, scope, or impact. A regime that compels the reporting of low-risk administrative errors risks conflating trivial incidents with materially harmful events. By reserving notification for circumstances in which high risk is present, the amendment ensures that regulatory and organisational resources are directed toward incidents where individuals’ interests are meaningfully at stake. This approach is more closely aligned with the normative logic of the Regulation, which emphasises context, severity, and likely consequences.

Second, the reform enhances legal certainty for organisations. The distinction between “risk” and “high risk” is conceptually subtle yet operationally consequential. In practice, organisations have frequently found the dual-threshold structure difficult to interpret, leading to conservative reporting practices. A single, clearly articulated standard reduces ambiguity, simplifies internal assessment processes, and supports greater consistency in decision-making. Legal certainty of this kind promotes better compliance outcomes by allowing controllers to focus on substantive risk evaluation rather than on navigating technical wording distinctions.

Third, the amendment alleviates unnecessary administrative burdens on Supervisory Authorities, enhancing regulatory efficiency. Current practice obliges regulators to process large volumes of notifications that provide limited regulatory value and do little to advance the protection of personal data. By filtering out low-risk incidents, the proposal would enable authorities to concentrate on serious breaches, systemic failings, and emerging threats. This reallocation of attention strengthens, not weakens, regulatory oversight by allowing resources to be applied where they yield the greatest public-interest benefit.

Importantly, the proposed change does not remove transparency or accountability from the breach management process. Article 33(5) GDPR continues to require controllers to document all personal data breaches, irrespective of whether they are notified to a Supervisory Authority or to affected individuals. This record must contain the facts relating to the breach, its effects, and the remedial action taken.

As a result, even where a breach is assessed as low risk and therefore not notified under the revised threshold, it remains subject to retrospective regulatory scrutiny. Supervisory Authorities retain the ability to verify compliance through complaint-handling, audits, or inspections by examining the controller’s breach register and assessing whether its risk assessment and decision not to notify were justified. The same documentation may also be reviewed where a data subject raises concerns about a breach that they were not notified about.

This continuing obligation functions as a substantive safeguard: it preserves accountability, ensures that low-risk breaches are neither ignored nor concealed, and maintains the institutional capacity of Supervisory Authorities to oversee organisational compliance notwithstanding the reduced volume of formal notifications.

The alignment of Articles 33 and 34 should be understood as an evolutionary rather than revolutionary development within the GDPR framework. It retains the commitment to transparency and accountability while recalibrating the regime to better reflect practical experience accumulated since the Regulation entered into force. In that sense, the proposal exemplifies regulatory learning: policy refinement informed by empirical realities and operational feedback.

However, it is essential to acknowledge that the Digital Omnibus proposal remains under negotiation and may be subject to amendment or reinterpretation before adoption. Stakeholders who recognise the benefits of this reform should therefore remain attentive to the legislative process and engaged in ongoing policy discussion. Until any amendment enters into force, the existing Article 33 standard continues to govern breach notification practice.

Raising the Article 33 breach notification threshold from “risk” to “high risk,” thereby aligning it with Article 34, represents a measured and intellectually coherent refinement of the GDPR’s breach notification architecture. The proposal enhances legal certainty for organisations, promotes proportionality in regulatory obligations, and reduces administrative burdens on Supervisory Authorities, enabling them to prioritise incidents that genuinely endanger individuals’ rights and freedoms. At the same time, the continuing obligation under Article 33(5) to document all breaches ensures that accountability and regulatory oversight remain intact, even when notification is not required.

The change deserves support as a pragmatic step toward a more balanced and risk-sensitive data protection regime. Yet it remains contingent upon the legislative outcome, and those who welcome the proposal should continue to monitor its progress to ensure that this alignment of thresholds is preserved in the final text of the Digital Omnibus package.

03 February, 2026

One of the most consequential — and potentially controversial — features of the European Commission’s Digital Omnibus proposal is the introduction of a new limitation to the data subject’s right of access under Article 15 GDPR. The proposal would allow restrictions where “the data subject abuses the rights conferred by this Regulation for purposes other than the protection of their data.”

For many organisations, this language speaks directly to a structural weakness in the current regime. Article 15 GDPR contains few intrinsic constraints on how the right may be exercised, while operational obligations on controllers are both strict and resource-intensive. As a result, organisations face a growing volume of repetitive, strategic, or dispute-driven requests that are only loosely connected to the transparency rationale of the right.

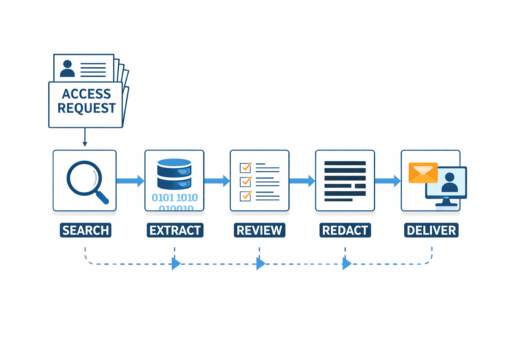

This concern is explicitly recognised in the Digital Omnibus. In its explanatory memorandum, the Commission notes that the abuse of data subject access requests “has frequently been raised as an issue for controllers who are required to dedicate significant resources to responding to abusive access requests.” In practice, responding to such requests involves system-wide data searches, extraction, review, redaction, coordination across systems and jurisdictions, and legal oversight — costs that are substantial and recurring, particularly in labour-intensive or highly regulated sectors.

From an industry viewpoint, the proposed limitation appears to be an attempt to restore proportionality to the access regime. The proposal targets contexts where access requests serve purposes disconnected from data protection, such as litigation strategy, employment leverage, broad discovery exercises, or commercial positioning, even when framed formally as transparency requests.

By signalling that the law may recognise and constrain abusive or strategically instrumentalised access practices, the proposal gestures toward a more sustainable, administrable, and operationally realistic framework. Many organisations will view this as an overdue corrective to a framework whose open-ended obligations have, in some cases, encouraged exploitation rather than accountability.

Any reform to the right of access must be assessed in light of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights (CFR). Article 8 CFR guarantees the right to the protection of personal data, including access to data concerning oneself. Further, Article 52(1) CFR, any limitation on a Charter right must:

The proposed restriction must therefore be evaluated not only in terms of administrative practicality, but also with regard to whether it:

The central challenge to determining when a request is abusive lies in the meaning to be drawn from the operative language. What does it mean to act for purposes “other than the protection of their data”? Does this include circumstances where the individual’s objectives are mixed — for example, where a request is connected to employment, consumer, reputational, or legal disputes, but the person still seeks meaningful information about the processing of their data?

Likewise, the term “abuse” is inherently open-textured. Without clearer statutory criteria, it risks beingdrawn too narrowly, neutralising its effect, or drawn too broadly, enabling controllers to reject requests that are burdensome but nonetheless engage the transparency function of Article 15.

From the standpoint of Article 52 CFR, this vagueness matters. The Court of Justice consistently requires that restrictions on fundamental rights be clear, predictable, and reviewable, so individuals can understand when and how their rights may be limited and so that arbitrary interference is avoided. A broadly framed concept of “abuse” may struggle to satisfy that standard unless later regulatory or judicial guidance supplies precision.

The Charter also requires that the essence of the right remain untouched. For the right of access, that essence is commonly understood as the individual’s ability to:

If the new clause were applied in a way that excludes requests merely because they arise in contentious or strategic contexts, there is a risk that access may be denied even where the substantive transparency interest remains real. In such scenarios, the restriction could drift from legitimate limitation toward structural erosion of a core accountability mechanism.

This is the fault-line on which the amendment will be judged: whether it targets only access requests that are functionally disconnected from the right’s purpose, or whether its breadth makes it difficult to guarantee that the right’s essence remains preserved.

A defensible proportionality rationale can nonetheless be articulated. Preventing the abuse of access rights may serve:

If the clause were narrowly interpreted, limited to cases where the exercise of the right bears no meaningful relationship to the protection or understanding of personal data, it could plausibly be seen as respecting the essence of Article 8 CFR, while ensuring that the limitation of the exercise of the right remains necessary and proportionate in practice, consistent with Article 52(1).

The difficulty is that the current drafting does not itself impose those limits, instead leaving the balancing exercise to future controllers, regulators, and courts, with inevitable uncertainty and litigation risk.

The Court of Justice has the opportunity to join the debate on proportionality and data access rights in the upcoming judgment in Case C-526/24 (Brillen Rottler), The Advocate-General’s opinion, issued in September 2025, tends towards maintaining few, if any, limits on the right of access. Given the facts of the case, where the abuse of access rights appears obvious, it is clear there is a long way to go before arriving at a workable solution.

For any reform to have constitutional durability, and practical usefulness, it will likely turn on whether the notions of “abuse” and “purposes other than the protection of their data” are ultimately narrowly delineated, applied with discipline, and anchored to preserving the essence of the right in line with Article 52 CFR.

Clearly, there is a need for greater precision on the meaning of the terms being applied in relation to data access rights. If that precision emerges during the current legislative debate, the reform may help restore a more sustainable balance between accountability and operational reality. If not, the clause risks being seen as too vague and open-ended to satisfy Article 52 CFR, and the debate over proportionality, necessity, and the preservation of the core right will only intensify.

The Digital Omnibus proposal acknowledges a real and pressing operational concern, one the Commission itself recognises as imposing significant, recurring costs on organisations required to respond to abusive access requests. It points toward a model more fitting to today’s hyperconnected world in which the right of access, as provided in the CFR, is preserved. However, the right of access needs to be exercised within clearer and more proportionate boundaries aligned with its core transparency function and work effectively in practice, to minimise abusive access requests.

15 January 2026

A simple assumption underpins how most people interact with information: if data is lawfully available to everyone, its reuse should not be treated in the same way as the use of private or confidential information. When individuals deliberately share personal data, such as publishing blog posts, authoring research papers, or sharing content openly online, they do so with the knowledge and expectation that this information will be seen, referenced, and reused.

Under GDPR, that assumption is often wrong. Publicly available personal data is frequently subject to almost the same legal constraints as data that was never meant to be disclosed at all. This reality is poorly understood outside specialist circles, and increasingly difficult to reconcile with both social norms and Europe’s broader regulatory objectives.

The legal source of this tension lies primarily in the purpose limitation principle in Article 5(1)(b) GDPR, which requires that personal data be collected for “specified, explicit and legitimate purposes” and not further processed in an incompatible manner.

GDPR does not relax this obligation simply because information is publicly available. Nor does it treat intentional publication by the data subject as a decisive legal differentiator. As the European Data Protection Board (EDPB) has consistently emphasised, personal data remains personal data regardless of its accessibility.

In practice, this means that a new use of publicly available personal data may still require a separate lawful basis and a compatibility assessment under Article 6(4), even where the data subject deliberately placed the information in the public domain.

Despite the centrality of purpose limitation in the GDPR, and its grounding in Article 8 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights, the EDPB has still not issued a dedicated, principle-level set of Guidelines on purpose limitation since the pre-GDPR period, as far back as 2013. Instead, the principle continues to appear only in passing within thematic texts. For example, in Guidelines 2/2019 on Article 6(1)(b) GDPR, the EDPB simply restates that “Article 5(1)(b) … requires that personal data must be collected for specified, explicit, and legitimate purposes and not further processed in a manner that is incompatible with those purposes”. This is a faithful formulation of the rule — but it remains interpretively thin when compared with the much earlier WP29 Opinion 03/2013, which is still the most detailed treatment of the principle but which clearly needs to be updated to take into account significant technological developments in the intervening 12 years.

A similar pattern appears in later texts. The EDPB’s draft Guidelines 1/2024 on legitimate interests incorporate purpose limitation mainly as a constraint within the Article 6(1)(f) analysis rather than as an independent doctrinal framework. And in Opinion 28/2024 on data protection aspects of AI models, the Board recognises that training datasets may include personal data “collected via web scraping”, but it does not clearly articulate how purpose limitation and the Article 6(4) compatibility test should apply to such large-scale secondary uses.

This absence of modern, standalone guidance matters. Purpose limitation directly challenges the assumption that publicly available data may be reused freely. The principle requires that any processing, even of information obtained from public sources, must remain tied to a specified, explicit and legitimate purpose, consistent with the context of collection and transparently communicated to individuals. Against rapidly evolving data ecosystems, the continuing reliance on a 2013 opinion underscores the case for the EDPB to provide updated, context-aware guidance on this foundational rule and how it should be applied.

This approach to publicly available personal information may be doctrinally coherent, but it is increasingly misaligned with policy reality.

Firstly, it creates a significant gap between public understanding and legal effect. Many organisations are surprised to learn that using information they can freely access, sometimes even information published by the data subject themselves, may still entail legal risk. This undermines trust in data protection law and contributes to the perception that it is detached from common sense.

Secondly, it generates unnecessary compliance friction, particularly for small and medium-sized organisations, researchers, and civil society. Actors engaging in low-risk reuse of public information must navigate complex legal assessments that add cost and uncertainty without clearly enhancing privacy outcomes.

Thirdly, it raises questions of regulatory prioritisation. When supervisory authorities devote time and resources to enforcing rigid restrictions on the reuse of public information, less attention is available for genuinely harmful practices involving sensitive data, coercive collection, or opaque processing.

These issues are directly relevant to ongoing discussions around GDPR reform and simplification, including the European Commission’s Digital Omnibus initiative and broader efforts to reduce regulatory burden while preserving EU fundamental rights.

Notably, recent policy debates have acknowledged, implicitly at least, that GDPR’s current framework struggles to accommodate how personal data is shared and used in today’s hyperconnected world. This is most visible in proposals to introduce a new or clarified legal basis for the use of personal data in the training of AI models, particularly where that data is lawfully available to the public. Such proposals are intended, in part, to overcome the rigidity of the purpose limitation principle when applied to large-scale, general-purpose reuse of information.

This recognition is important. It reflects an emerging consensus that applying purpose limitation too strictly to publicly available information can produce outcomes that are disproportionate, impractical, and detached from risk.

However, focusing narrowly on AI model training misses the broader point. The tension between purpose limitation and public information is not confined to any single technology or sector. It affects research, market analysis, public-interest investigations, archival work, and a wide range of ordinary, low-risk further processing of information that individuals and organisations have intentionally made public.

In other words, the problem is not only technological, it is structural. Creating a bespoke legal basis for one category of processing may address a specific pressure point, but it leaves untouched the underlying issue: GDPR lacks a clear, context-sensitive approach to how personal data intentionally made public should be treated.

If reform efforts are limited to carve-outs for particular use cases, they risk adding complexity. A more durable response would align with the stated objectives of the reform agenda itself—legal certainty, proportionality, and effective enforcement—by clarifying how purpose limitation should operate where data subjects have deliberately placed information in the public domain.

GDPR already contains concepts that could support a more balanced approach. Articles 5(1)(a) and 6(4) refer to fairness, proportionality, and reasonable expectations. Recital 47 explicitly links legitimate interests to what data subjects can reasonably expect. In practice, however, these concepts rarely override purpose limitation when public data is involved. Intentional publication is treated as legally incidental rather than substantively relevant.

A failure to clarify the application of purpose limitation to public information is a missed opportunity. Information that is deliberately made public carries different expectations and typically presents lower risks than information disclosed under necessity or obligation. Failing to reflect this distinction does not strengthen protections—it blurs them.

None of this argues for exempting publicly available personal information from data protection law. Public data can still be misused, aggregated harmfully, or processed in ways that undermine dignity and autonomy.

But regulation should be risk-based and context-sensitive. A more proportionate approach would:

These changes could largely be achieved through interpretative guidance, without reopening the GDPR’s core architecture.

As the EU considers how to modernise and simplify its data protection framework, the treatment of publicly available personal data deserves more systematic attention. GDPR already contains the conceptual tools—fairness, proportionality, reasonable expectations—to support a more balanced approach. What it lacks is a willingness to let context play a decisive role outside sector-specific exceptions.

Addressing the reuse of public information solely through technology-specific legal bases risks treating symptoms rather than causes. The credibility of data protection law depends not only on safeguarding EU fundamental rights, but on doing so in ways that are intelligible, proportionate, and aligned with social reality. Recognising that public information is not the same as private information is not a concession to innovation pressures. It is a necessary step toward a data protection regime that is both effective and sustainable—regardless of the technology involved.

23 December, 2025

Under the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), processing personal data is lawful only if it falls within one of six legal bases set out in Article 6(1). These are: consent, contractual necessity, legal obligation, vital interests, public task, and legitimate interests. Consent is often treated as the most ethically appealing of these bases, rooted in individual autonomy and control. Unlike other legal bases, which depend on institutional roles or balancing tests, consent places the data subject at the centre of the decision-making process.

Consent sits at the moral heart of the GDPR. Few ideas feel more intuitively aligned with data protection than the notion that individuals should control how their personal data is used. In theory, consent empowers users, disciplines organisations, and anchors data processing in respect for autonomy. In practice, however, GDPR consent has become one of the most fragile and contested lawful bases for processing personal data. Precisely because consent is framed as an expression of personal choice, GDPR imposes particularly demanding conditions on its validity. These conditions—requiring consent to be freely given, specific, informed, and unambiguous (Article 4(11))—have transformed consent from a flexible enabler of data processing into one of the most difficult and risky legal bases to rely on, especially in the modern digital environment.

The reason is not philosophical opposition to consent itself, but the cumulative weight of the legal standard imposed upon it. Each requirement is defensible in isolation. Taken together, especially in the context of modern digital systems and rapidly evolving technologies, they set a bar that is often unrealistically high. This has made consent difficult to rely on, risky to operationalise, and in some cases counterproductive to the very goal of meaningful user protection.

Consent must be freely given, meaning that the individual must have a genuine choice and must not suffer detriment if they refuse. On its face, this requirement is intended to prevent coercion and abuse. In practice, it has become one of the most destabilising elements of GDPR consent.

Regulatory guidance, particularly from the European Data Protection Board (EDPB), emphasises that consent is invalid where there is a clear imbalance of power between the data controller and the data subject. This logic is uncontroversial in contexts such as employment or public services. However, it has increasingly been extended into the digital commercial sphere, where power imbalances are more nuanced.

Many online services are functionally unavoidable. Social networks, communication tools, professional platforms, and cloud-based services play a central role in economic and social participation. If access to such services is conditional on consent to extensive data processing, regulators increasingly question whether consent is truly free, even if users technically have the option to walk away.

This creates a structural problem. Digital services are often built around data-intensive business models. Advertising-funded platforms, AI-driven personalisation, and security or fraud-prevention systems all rely on continuous data flows. As regulators narrow the scope of what counts as “strictly necessary,” consent is more readily deemed invalid because users are said to lack a meaningful alternative.

The result is a paradox: the more sophisticated, integrated, and widely used a service becomes, the harder it is to argue that consent to its data practices is freely given. What was intended as a safeguard against coercion risks becoming a blanket scepticism toward consent in almost any commercial digital context.

The GDPR requires consent to be specific, meaning it must be tied to clearly defined purposes. Where multiple purposes exist, separate consent may be required. This requirement reflects a legitimate concern that individuals should not unknowingly authorise unrelated or unexpected uses of their data.

However, modern data processing rarely fits neatly into discrete, static purposes. Digital services are complex systems involving overlapping functions: service delivery, security monitoring, analytics, product improvement, regulatory compliance, and increasingly, machine learning and artificial intelligence.

Attempting to map this complexity into narrowly defined purposes that are both accurate and understandable is exceptionally difficult. Organisations face a choice between excessive granularity and excessive abstraction. Overly granular consent requests fragment processing into dozens of categories, overwhelming users and encouraging mechanical acceptance. Overly abstract purposes, meanwhile, are vulnerable to regulatory criticism for being insufficiently precise.

The challenge is particularly acute for AI-driven systems. Data may be reused to train, test, or improve models in ways that are not fully foreseeable at the point of collection. Requiring consent to be specific in advance assumes a level of predictability that modern data innovation often lacks.

As a result, specificity becomes less a tool for user empowerment and more a compliance trap, where organisations struggle to strike an acceptable balance between legal precision and operational reality, degrading the user experience in the process.

For consent to be valid, individuals must be informed. This includes understanding who is processing their data, what data is involved, for what purposes, and what the consequences may be. Information must be provided in clear and plain language.

The difficulty is that many contemporary data processing activities are technically complex, probabilistic, and opaque even to specialists. Explaining algorithmic inference, data sharing ecosystems, or automated decision-making systems in a way that is both accurate and accessible to a general audience is an extraordinary challenge.

Organisations are therefore caught between two unsatisfactory options. They can simplify explanations to make them readable, risking accusations that they are misleading or incomplete. Or they can provide lengthy, technically detailed disclosures that are legally defensible but practically useless, as few users read or understand them.

Regulators often assess whether consent was “informed” from a legal and technical standpoint, while users engage with consent notices through quick, habitual interactions. This mismatch turns informed consent into a legal abstraction rather than a lived reality.

The requirement that consent be unambiguous demands a clear affirmative act by the user. Pre-ticked boxes, silence, or inactivity are insufficient. This standard has reshaped digital interfaces, from cookie banners to app permissions and sign-up flows.

While this has eliminated certain abusive practices, it has also normalised constant consent prompts. Users are asked to click “Accept” repeatedly across websites and applications, often multiple times per day.

The result is not heightened awareness, but desensitisation. Affirmative action becomes a reflex, not a considered choice. The legal clarity sought by regulators does not translate into meaningful engagement by users.

At the same time, the margin for error is narrow. Small design choices—button placement, wording, or default settings—can determine whether consent is deemed valid or unlawful. This creates a fragile compliance environment in which formalism outweighs substance.

Each element of GDPR consent—freely given, specific, informed, and unambiguous—serves a legitimate protective purpose. The problem arises when they are applied cumulatively, without sufficient regard for how digital services actually operate.

Together, they create a standard that is extremely difficult to satisfy with confidence. As a result, many organisations increasingly avoid consent altogether, turning instead to other legal bases such as legitimate interests or contractual necessity, even in situations where consent might seem intuitively appropriate.

This outcome is deeply ironic. Consent, intended as the gold standard of user control, has become the most legally precarious option. Users, meanwhile, are inundated with consent requests that provide little real choice or understanding.

The challenge of GDPR consent is not that the concept is flawed, but that the regulatory bar has been set without sufficient consideration of technological complexity, human behaviour, and innovation dynamics. By insisting that consent simultaneously meet four demanding criteria in environments where none are easy to satisfy, the GDPR risks hollowing out consent’s practical value. In an environment where even well-intentioned transparency efforts struggle to convey genuine understanding, the expectation that users can make informed choices about complex data practices becomes increasingly unrealistic.

A more sustainable approach would recognise the limits of consent as a governance tool and place greater emphasis on accountability, proportionality, and substantive protections regardless of the legal basis relied upon. Without such recalibration, in the digital age, GDPR consent will remain a powerful idea burdened by an unrealistically high standard.

8 December 2025

Europe’s ambition to lead in trustworthy AI sits uneasily beside one of its oldest privacy rules: data minimisation. Like its sibling principle, purpose limitation, it was drafted in an analogue world — when computer memory was expensive and data collection was clumsy.

In the era of machine learning, the rule that data must be “adequate, relevant, and limited to what is necessary” (GDPR Article 5(1)(c)) is colliding with the realities of modern innovation. In Opinion 28/2024, the European Data Protection Board (EDPB) highlighted the importance of the data minimisation principle, even in the context of AI development and deployment. Yet AI thrives on more, not less — more variety, more volume, more iteration. If Europe insists on training tomorrow’s AI with the data philosophy of yesterday, it risks building the world’s most ethical technology that no one actually uses.

Data minimisation was born out of a perfectly rational fear: the rise of computerised government databases in the 1960s and 70s. Early data protection laws, from Sweden’s 1973 Data Act to the OECD Guidelines (1980) and the Council of Europe’s Convention 108 (1981), all shared the same goal — stop bureaucracies and corporations from gathering and storing excessive amounts of personal information. Back then, more data meant more danger. Each record carried risk; storage was costly; and state surveillance, not statistical insight, was the primary threat. The regulatory philosophy was simplistic and moral: collect only what you need, for as long as you need it.

By the time the GDPR took effect in 2018, the digital world had turned that logic upside down. Storage was cheap, computing was fast, and data had become the raw material of innovation. Yet Europe kept the same guiding principle, barely touched since 1980.

The problem is not that minimisation is wrong, it is that it’s anachronistic. The data minimisation principle assumes that the value of data is known in advance and that collecting “too much” creates risk without benefit. But in AI, the relationship is reversed: we often don’t know which data will matter until after the model learns from it. AI models need data that are diverse. Limiting data collection too tightly risks producing biased, inaccurate, or fragile systems. Precisely the sort of AI development Europe says it wants to avoid, in order to extract the benefits of innovation.

The EDPB, however, maintains a strict line, the data minimisation principle still applies.

Three structural features of the digital era make the minimisation rule increasingly unworkable:

The irony is sharp: a rule designed to protect individuals from data misuse now risks depriving them of the benefits of responsible data use — from better healthcare diagnostics to climate modelling to AI technology.

In short, Europe’s devotion to small data may be producing small results.

In the global AI race, the consequences are visible.

Europe’s advantage in regulation has become its disadvantage in innovation.

Europe does not need to abandon privacy to stay competitive — it needs to modernise how it interprets its principles. Europe’s approach to AI development should not prioritise minimal data but must demand responsible data.

Pragmatic reforms could align data minimisation with digital reality. Such reforms might focus on increased risk-based interpretations that shift the focus from data quantity to risk mitigation. They might also include dynamic proportionality tests, allowing broader data use when clear societal benefits and public interests are at stake. And moving away from compliance checklists to outcome based accountability, giving AI developers flexibility whilst preserving public trust.

These changes would align the GDPR’s spirit — protecting individuals — with its new context: enabling responsible AI that benefits them.

The principle of data minimisation clearly made sense in the fledgling days of digital technology but the technologies we now seek to regulate have changed beyond recognition. Europe is trying to train modern AI under rules written for another era. Insistence on ever-smaller datasets in the name of privacy might deliver the cleanest compliance record, but at the cost of innovation.

Less data may mean more virtue — but it also means less progress.

17 December 2025

In the recently released Digital Omnibus, the Commission proposes amending the definition of personal data in article 4(1) of the GDPR. The revision includes further text to clarify that information about a natural person is personal data under the GDPR only if an entity can realistically identify the individual. The revision seeks to emphasise that identifiability is context-dependent and not universal for all recipients.

This proposal is a result of the recent judgment by the Court of Justice (CJEU) in EDPS v SRB (C-413/23). This case clarified prior judicial decisions on this matter, confirming that the definition of personal data in the EU is based on a “relativist” approach that is both context-sensitive and recipient-specific. While this case focused on the application of Regulation (EU) 2018/1725, this regulation directly mirrors the GDPR and creates similar obligations for application.

The case arose after the Single Resolution Board (SRB), an EU body, collected comments from stakeholders during the resolution of Banco Popular Español. These comments, which included personal opinions, were pseudonymised (identifiers replaced with codes) and transferred to a consultant for analysis. In this transfer, SRB alone held the necessary key to re-link the codes to individuals. Following complaints from individuals involved in the resolution, the European Data Protection Supervisor (EDPS) found that the SRB had breached transparency obligations by failing to disclose that the data had been sent to a consultant. The General Court initially annulled the EDPS decision, holding that the data had been anonymised when transferred to the consultant.

The EDPS appealed to the CJEU, which provided a nuanced interpretation of what constitutes personal data. The CJEU’s judgment is notable for its explicit endorsement of a relativist or context-dependent” approach to personal data. Rather than treating identifiability as an absolute, the Court held that whether information is personal data depends on the specific context and the recipient’s ability to identify individuals using “means reasonably likely to be used”. The Court’s approach is dynamic, reflecting the practical realities of modern data processing.

The Court of Justice based its decision in its earlier decision in the case of Breyer (C-582/14) from 2016. In Breyer, the Court held that information can qualify as personal data even when identification requires access to additional data held by a third party, provided that identification is “reasonably likely” given the means available. The EDPS v SRB judgment confirmed that identifiability is not a binary or abstract matter, but a relational question. Instead of creating an absolute marker for all personal data, the Court makes clear that realistic questions must be asked, such as: to whom is it identifiable, by what means, and in what context? If adequate measures are taken by a data controller that mean a particular recipient cannot re-identify individuals, then for that recipient, the data are not personal.

The judgment in EDPS v SRB brings several important clarifications to the understanding of personal data under the GDPR. It confirms that personal opinions or views, as expressions of an individual’s thinking, are inherently linked to their authors and therefore constitute personal data, even when presented in pseudonymised form. Pseudonymisation, while a valuable technical and organisational safeguard to reduce the risk of re-identification, does not automatically remove data from the scope of the GDPR. Instead, the legal status of such data depends on whether the recipient can realistically re-identify the individuals concerned. The obligation to inform data subjects about the recipients of their data remains with the controller. It must be fulfilled at the time of collection, regardless of whether the data is later transferred in pseudonymised form. There is no blanket exemption for downstream recipients. Pseudonymised data may not be personal for a recipient who lacks the means to re-identify individuals, this does not absolve the original controller from their responsibilities under EU law.

The practical implications of this relativist approach are both flexible and complex. Controllers must assess identifiability from their own perspective to meet transparency obligations and cannot rely on downstream pseudonymisation to avoid disclosure duties. Recipients, on the other hand, must carefully evaluate whether they truly lack the means to re-identify individuals, taking into account the possibility of cross-referencing with other datasets, technological capabilities, and legal access to additional information.

For data subjects, the judgment strengthens transparency rights, ensuring that controllers cannot circumvent disclosure obligations through technical measures applied after collection. However, this context-sensitive approach introduces operational complexity, as a dataset may be considered personal for some actors and not for others. This complicates processing chains, data clean rooms, and arrangements for training AI models. As a result, organisations must document their risk assessments thoroughly and maintain evidence of their analysis regarding the means reasonably likely to be used for re-identification.

The EDPS v SRB judgment is a clear reminder that data protection, in itself, is not the only objective to be pursued, and that the practical realities of data processing must be recognised. By reaffirming a context-dependent approach, the CJEU has clarified that personal data is not an absolute characteristic but one that depends on the circumstances of processing and the realistic means of identification available to the relevant actor. Under the absolutist approach, if anyone could, in principle, re-identify individuals from a dataset, it should be classified as personal data for everyone, regardless of the recipient’s actual capabilities. This approach maximises protection but increases regulatory burden and may restrict beneficial uses of data.

The relativist approach, by contrast, supports flexibility and proportionality, enabling broader data reuse—especially in analytics and research—while still preserving core protections. However, legal protection for data remains strong, as there is an evidential burden on controllers to show that re-identification is not reasonably likely.

Including the CJEU’s approach in clarifying the definition of personal data in the GDPR is to be welcomed. Not only is the Court’s decision the highest legal standard in the EU, but it will also require many national authorities to reconsider their approaches to personal data. For organisations processing data, the relativist approach provides greater flexibility but also greater responsibility to carry out robust, documented risk assessments. For data subjects, the judgment enhances transparency and ensures that data protection rights cannot be circumvented solely by technical measures. As data ecosystems grow ever more complex, the CJEU’s approach offers a nuanced, risk-based path forward for a more realistic EU data protection law.

29 November 2025

The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) grants individuals important powers over their personal information. Among the most central are the rights to rectification (to correct inaccurate data) and erasure (to request deletion). These protections aim to ensure fairness by preventing outdated or incorrect information from influencing meaningful decisions about people’s lives.

The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) grants individuals important powers over their personal information. Among the most central are the rights to rectification (to correct inaccurate data) and erasure (to request deletion). These protections aim to ensure fairness by preventing outdated or incorrect information from influencing meaningful decisions about people’s lives.

Yet while these rights remain essential, the context in which they operate has changed dramatically. Much of the GDPR rests on assumptions formed when personal data was simpler, more factual, and easier to control. Today, information is continuously generated, widely shared, and stored across complex digital infrastructures. The gap between what the law expects and what modern technology can realistically deliver is becoming increasingly difficult to ignore.

Rectification and erasure rights emerged in the 1970s and 1980s, when European countries first introduced rules to protect citizens from the misuse of personal information. At that time, the nature of data and data systems made such rights straightforward to administer. Most information held by organisations was objective—names, addresses, financial records. Systems were centralised, databases were traceable, and if something was wrong, it could usually be corrected; if something needed to be deleted, it could genuinely be removed.

These early rights were later absorbed into the GDPR with broader scope and stronger enforcement. What did not carry forward, however, was a fundamental updating of the assumptions about how data behaves.

The nature of personal information today is fundamentally different. Three shifts are particularly significant.

First, personal data is no longer purely factual. Many of the data points used by organisations are interpretations or predictions—such as inferred interests, behavioural classifications, or machine-generated risk scores. These categories are not easily labelled as “correct” or “incorrect”, which complicates the idea of rectification.

Second, data no longer sits in one place. Once collected, information can be spread across multiple systems, shared with vendors, stored in automated backups, and used to train analytics or machine-learning models. Organisations often struggle to map where every copy resides.

Third, modern systems are interconnected and automated. A correction in one database may not propagate through others. Some information must be retained for compliance, fraud prevention, or auditing reasons even after an erasure request is made. The infrastructure itself makes perfect rectification or deletion difficult to guarantee.

These realities transform the practical meaning of rights that were designed for a different technological era.

Public trust in digital services depends heavily on confidence that personal information is handled responsibly. When individuals find they cannot reliably correct or delete their own data, that confidence erodes.

There are also significant operational consequences. Organisations expend vast amounts of time and resources searching for data that may be fragmented or duplicated beyond traceability. Individuals grow frustrated when their expectations of control do not align with the technical realities. Regulators, meanwhile, face enforcement challenges when compliance cannot be fully demonstrated.

The result is a system where rights exist in principle but may be difficult to guarantee in practice.

Maintaining the value of rectification and erasure requires updating these rights to reflect how data actually works today. Several principles could guide such reform.

A first step is distinguishing between types of data. Objective information—such as an address or account detail—should remain fully correctable. Subjective or inferred information may instead require transparency, explanation, or the ability to challenge its use, rather than literal rewriting.